Advanced Research for Climate Emergencies

The world needs an ARPA for Climate, its just not the one we thought

The real-time consequences of delayed climate action have become impossible to ignore. Dire warnings from scientists about the increasing risk of unacceptable, and in some cases unimaginable, climate impacts are growing ever more frequent1: catastrophic sea level rise2, large-scale loss of arable land or critical freshwater sources3, regional feedback loops that could drive rainforest dieback or uncontrollable methane emissions4, or earth system changes in the ocean or Arctic that could drive unpredictable large-scale changes in severe weather5 (just to name a few). Most (though probably not all6) of these many climate impact emergencies could be abated by some combination of a rapid reduction in emissions and an escalation of direct CO2 removal from the atmosphere. But the political, economic and technical barriers, combined with continued uncertainty about safe temperature thresholds for various parts of the earth system, mean that the risk of triggering one or more climate impact emergencies in the next two or three decades remains high.

Existing institutions are not well suited for addressing climate impact emergencies.

Catastrophic risk is the ultimate “wicked problem”, highly complex (and strongly coupled) non-linear systems, deep uncertainty, few (if any) historical analogs and events unfolding on time-scales far beyond those that usually motivate Washington (i.e. election cycles if you’re feeling particularly pessimistic). Decision-makers at national and even intergovernmental levels that have some mandate and authority to address these risks are generally either distracted by more immediate issues, feel constrained by political realities, find the issues too complex or intractable, or find some way to discount the threats posed by climate impact emergencies (for example, by asserting that acknowledging catastrophic risk could lead to public resignation that would impede climate action)7. Climate risks at this scale lack clear ownership by any one part of government, and policymakers preoccupied with the needs of day-to-day governance generally don’t even have the data or tools necessary to deeply understand the risk, never mind the robust planning frameworks necessary to address them. The result is a status quo of avoidance and inaction.

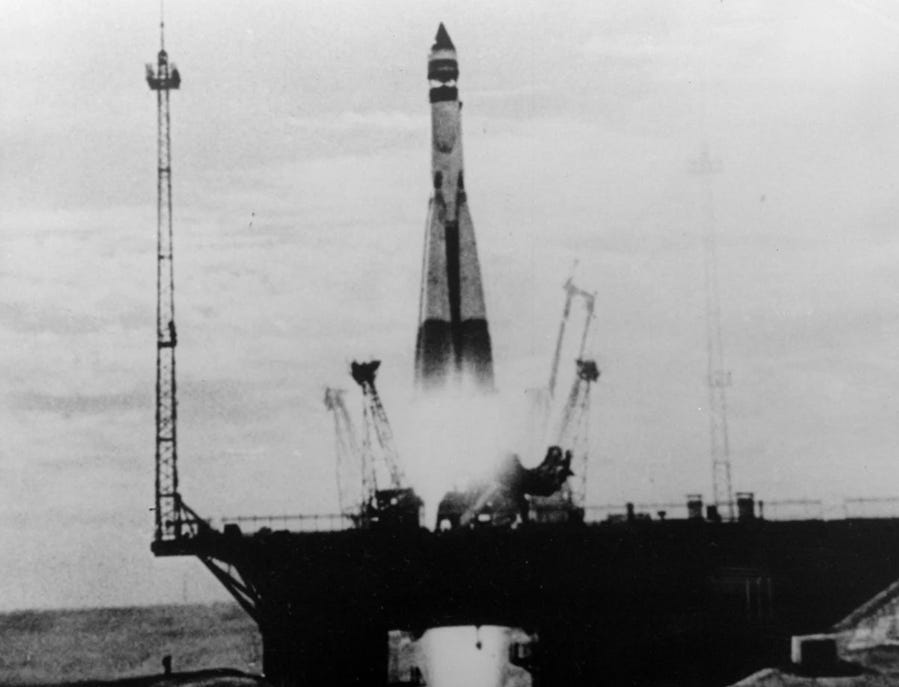

The ARPA analog: Urgency and the “Sputnik moment”

A similar complacency was pervasive in the US national security establishment of the 1950s regarding the state of the Soviet rocket program. The successful launch of Sputnik in 1957, a technological feat and strategic coup with potentially huge economic and defense implications, shocked the US government and the world. Just 4 months later President Eisenhower signed the order creating the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), tasked to pursue beyond-the-cutting-edge research programs designed to ensure that we were never surprised like that again.

The world desperately needs a similar urgency now to avoid potential climate impact

emergencies that would amount to strategic surprise at a truly planetary, catastrophic scale.

ARPA (the ‘D’ was added in the 70s, then briefly removed and added back in the 90s) was created precisely to think about the big future strategic risks (and opportunities) that no one else was thinking about and conduct ambitious R&D programs well in advance to address them. The mission fundamentally requires a substantial amount of speculation (e.g. about future world states, adversary capabilities and the boundaries of science and tech) and the programs inevitably have a high risk of “failure”8 to go along with their potential for huge reward. This required a very different type of agency that could act with significant autonomy, be largely shielded from the whims of politics (even through the occasional controversy around its work) and incentivize its Program Managers to try big ambitious things without fear of failure. Early leaders developed the concept of “ARPA hard” to ensure that programs were sufficiently ambitious, both in terms of technological challenge and impact. Any program deemed too easy (i.e. low-risk) or low-impact to be ARPA hard is scrapped pretty quickly. We used to say that a good DARPA program had 1 or maybe 1.5 aspects to it that sensible people deemed impossible9.

Early in the Biden administration there was talk of creating an ARPA for climate (ARPA-C10). But initial proposals struggled to distinguish themselves from the mandate of ARPA-E (i.e. it was focused largely around electrification, clean energy and storage, energy efficiency, carbon capture and land-use change, areas that ARPA-E already lays some claim to). Political and bureaucratic challenges, combined with the lack of a clear champion in the administration, meant the proposal was effectively DOA.

The problem (or one of them) is that “climate” is so incredibly broad, potentially touching every aspect of our society: energy, infrastructure, food, water, health, national security, coasts, fires, ecosystems, livelihoods (and on and on). As most people with experience will tell you, a key ingredient of a good ARPA is a focused and clear mission that can guide the development of programs in what is otherwise a very open-ended model for translational R&D (the story of HSARPA in the Department of Homeland Security is a good cautionary tale11).

What if we instead imagine an ARPA-C based on directly addressing the risks of strategic surprise from emergency climate impacts? This would be clearly distinguished from any other research enterprise and have a clear and focused mission and mandate. And because the mission is about potential risks in the future (hopefully far-future in most cases, but definitely not all), it requires speculating strategically and creatively about these possible futures, and designing R&D programs now that have a chance to address the risks. It is, in various ways, precisely the kind of fundamentally speculative high-risk, high-reward endeavor that the ARPA model was designed for in the first place. Unfortunately there’s little sign of the urgency and political will that such an endeavor would require.

Do we really still need a “Sputnik moment” to generate the urgency the world needs? Can we afford to wait until Dhaka is underwater, the Amazon is half-gone, the tundra is pockmarked by methane bursts, or the Arctic is ice-free? We have to act now.

The risk of “cowboy solutions”

Recently, a broad and largely uncoordinated group of private donors are beginning to step into this vacuum, producing (or proposing) funding for advanced research in various categories of emergency climate options (ECOs) with the potential to temporarily counter anthropogenic warming (globally or in key regions like the Arctic), address catastrophic sea level rise scenarios, restore degraded lands, or replace or restore key freshwater resources. While this private philanthropy is generally positive, there are valid concerns that poorly targeted programs from organizations and individuals that lack critical accountability, domain expertise or close coordination (between efforts and with relevant parts of government) could make mistakes that could set the field back or, much worse, cause real damage. While we can imagine a few ways to respond to this challenge/opportunity, the key immediate need is increased capacity for translational R&D that is mission-driven, urgent and responsible, combined with mechanisms and forums for improved coordination, deliberation (e.g. on standards of norms and safety), government engagement and policy advocacy.

The key immediate need is increased capacity for translational R&D that is mission-driven, urgent and responsible.

So what can we do?

While the ultimate goal is to convince governments (particularly the US) to take on this challenge head on, we simply can’t afford to wait. One approach we’re really excited about is the potential to create a philanthropically-supported ARPA-inspired entity that can get started now on this important work while simultaneously building the case for governments to get serious about translational R&D for climate emergencies. We’re calling this idea the Advanced Research for Climate Emergencies (ARC) concept.

Its reasonable to assume that we have about 10-15 years to advance potential emergency options to a point where they can be safely operationalized and scaled, should they be needed. This represents a tight timeline for “ARC hard” problems.

An ARC would operate as a coordinating hub for ECO R&D, building partnerships across philanthropy, governments and the broad cross-section of the science and engineering ecosystem that will be essential for ECO R&D programs to succeed. It would scope, incubate and launch programs, create risk assessments and roadmaps (where they don’t exist), convene inclusive goal-oriented workshops to bridge gaps across the key stakeholder groups, and work with top scientists to design, staff, train, fund and support mission-focused translational R&D programs across the landscape of potential ECOs. An ARC could also work closely with program leaders to help translate important developments for funders, policy-makers and the broader stakeholder community.

For most unacceptable or existential climate risks, its reasonable to assume that we have about 10-15 years to advance the R&D, political acceptance and social license of potential emergency options to a point where these approaches can be safely operationalized and scaled (by governments with, in some cases, the support of markets), should they be needed. In some cases ARC programs may very well try to take ECOs all the way to the demonstration scale, while in other cases the goal may be to prove (or disprove) key aspects of safety, feasibility or effectiveness. Either way, its fair to say this represents a tight timeline for “ARC hard” problems.

Here are some examples of the types of things we’re thinking about that could be high priorities for ARC-style programs:

Preventing catastrophic sea level rise (by addressing factors destabilizing polar ice sheets)

Countering inevitable sea level rise to protect large coastal populations and island nations (e.g. through restoring inland seas)

Enhancing reflectivity, regionally or globally, to counter further warming and keep temperatures as close to safe levels as possible (e.g. with stratospheric aerosols, marine cloud brightening, cirrus and mixed-phase cloud thinning, optimizing existing aerosol sources, large-scale surface albedo, etc.)

Restoring degraded or desert lands or watersheds for sustainable agriculture and other uses (e.g. through re-flooding inland seas, heat/moisture compensation, river restoration, large-scale soil amendments, etc.)

Restoring the Arctic (e.g. sea ice thickening, tundra resilience, albedo modification, etc.)

Fast-acting options for large-scale carbon cycle enhancements (e.g. w/ ocean nutrients)

Comprehensive assessment of catastrophic climate change emergencies (and options) to support policy-makers in planning under deep uncertainty.

Engineering urban cooling at scale

If you have ideas for ARC-style topics or how to get potential programs off the ground or if you’re just interested and want to stay informed, please don’t hesitate to reach out through our website: https://arc-init.org/.

https://www.pnas.org/doi/abs/10.1073/pnas.2108146119

https://www.cell.com/one-earth/pdf/S2590-3322(20)30592-3.pdf

https://www.unccd.int/news-stories/press-releases/drought-data-shows-unprecedented-emergency-planetary-scale-un

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41558-022-01512-4

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/extreme-cold-snaps-could-get-worse-as-climate-warms/

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-018-08195-6

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-challenging-politics-of-climate-change/

Or at least perceived failure: much has been written about the challenges of defining impact and success from these sorts of efforts, my favorite of which is by my friend and ARPA PM extraordinaire, Adam Russell (https://issues.org/arpa-intelligible-failure-russell/).

2 impossible things means you may actually have 2 different programs

https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/02/11/biden-harris-administration-launches-american-innovation-effort-to-create-jobs-and-tackle-the-climate-crisis/

https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/details?prodcode=R43064